This text is presented in two languages. I wanted to keep the original in Spanish because that’s the language in which I wrote it. But I also wanted to translate it so it could reach my dear English-speaking readers. I’m not a professional translator! But I’ve tried to keep my original tone. It’s never quite the same to write in a language that isn’t your mother tongue—some things can’t be said in the same way.

For Heaven only knows why one loves it so, how one sees it so, making it up, building it round one, tumbling it, creating it every moment afresh; (…) what she loved; life; London; this moment of June.—Mrs. Dalloway, Virginia Woolf

There’s a room facing east at my parent’s flat from which you can, through the almost square window, catch a glimpse of part of the Serra de Vernissa and a few of the ancient walls of El Castell, which carves the ridge of the mountain and remains the pride of els socarrats, us, its inhabitants, overlooking our land.

The arrival ritual is always the same: my parents pick me up at Valencia airport, we load the suitcases into the car, and head down to Xàtiva—always making a mandatory stop to pick up a bocaillo near Alberic. There are some things one simply doesn’t want to change, and one of them—besides the ritual itself—is the iconic view of the village (or town, as I’m always told to say) upon arrival, just as you take the motorway exit. That’s when the whole of Xàtiva comes into view, resting along the edge (a la voreta) of the mountain, as if it had always been there, with the castle framing and carving out the mountain’s natural silhouette, surrounded by orange trees and a few other citrus plants.

Coming back is also a journey through time. That’s why, every time I return, I find myself asking: where am I from now? From there, or from here? And what even is there or here? Where’s my relative position in all of this?

Ilu Ros recently published Una casa en La Ciudad, a beautiful story I stumbled upon by chance at the Fnac, one of those days we spent wandering around Valencia. I stand by what I’ve said before: those special books that leave a mark, that teach you how to look, they always arrive at the right time, in the right place—just like the great loves of one’s life. Funnily enough, La Ciudad (The City) that remains unnamed in Ilu Ros’s story is none other than my beloved London.

Una casa en La Ciudad (A House in The City) is about the search for a place in the world, and the realisation that life is nothing but what happens along the way during that very search.

Ilu’s story is so powerful because she is, in fact, telling the story of many of us who have emigrated. We have asked—and keep asking—the same questions. I was fortunate enough to arrive in London at a different time and under different circumstances, avoiding many of the hardships that Ilu describes in her book (something that has filled me with immense gratitude and deep empathy). Yet the questions and reflections are exactly the same. And so, too, are the conclusions. She writes:

I want to stop time. Their time. The time of those who stay behind while I return to The City. Freeze them, like a photograph. So they can’t keep living without me, so I won’t miss all the things that happen to them when I’m not there.

I consider The City—London—my home. I feel that coming back home has been, for some years now, going—returning—to London. When I come back to the land where I was born, Xàtiva, very little has changed, except for people on the outside. The passing of time leaves a sharp trace on all of us. But going—or returning—after having once left gives you a wonderful advantage: the ability to see through, to see the world—this world—from a different perspective. Or rather, through a different lens.

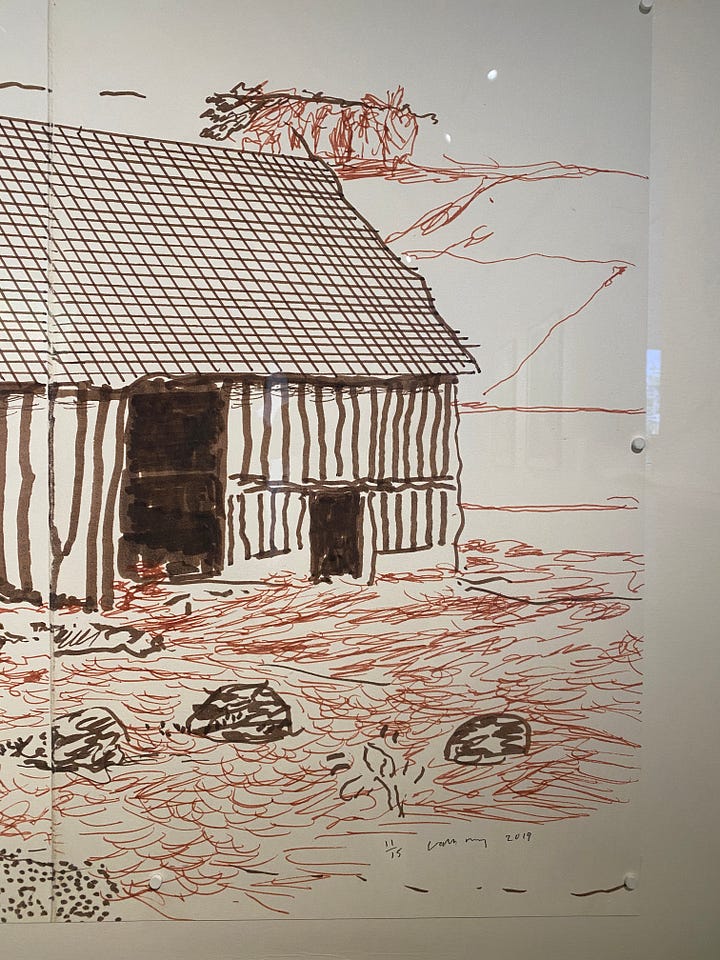

That’s exactly what we learn through drawing. Drawing is nothing but learning to see—to see the essence of things, and to see them as we want them to be too. David Hockney (there he is again!) is one of those artists who believes that a drawing is more real than a photograph, precisely because it embeds human experience directly through the artist’s hand.

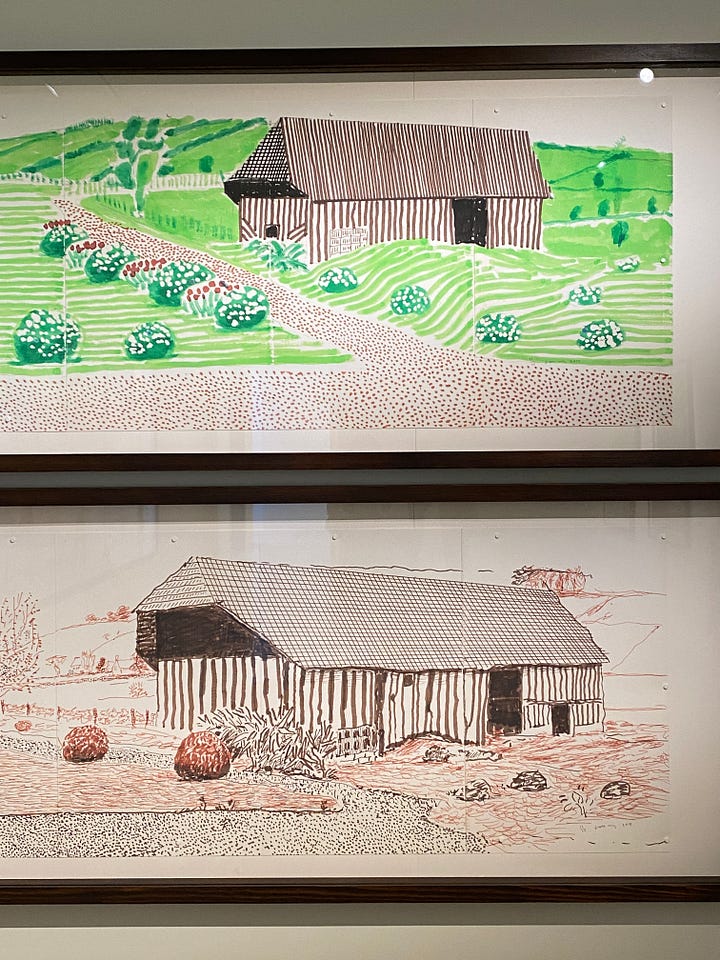

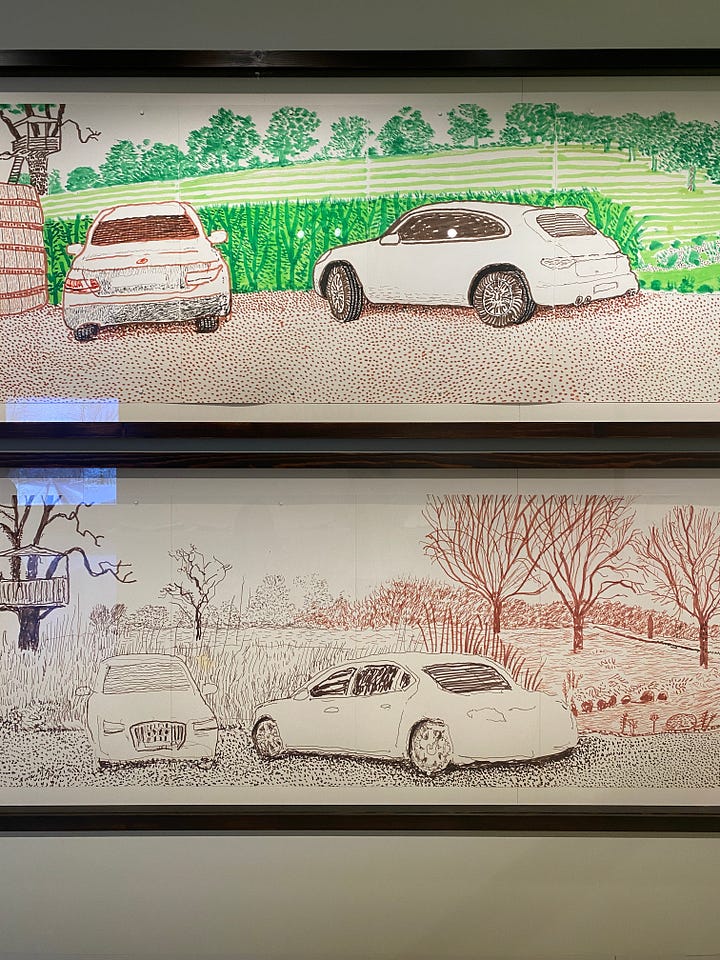

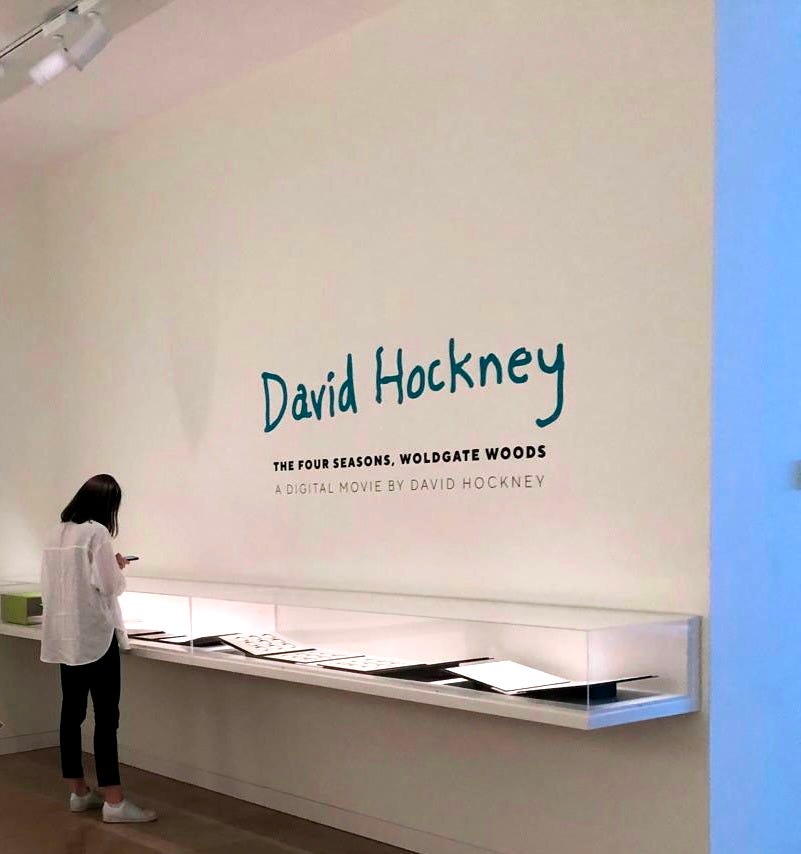

On this very trip back to my terreta for a few days, I had the pleasure of visiting a contemporary art gallery in Valencia, the Centro de Arte Hortensia Herrero. In room 12, you can find a small treasure: a couple of panoramic drawings that Hockney created of his house in Normandy, during The Arrival of Spring. I had seen these drawings hundreds of times before in his book of the same name, which I have recommended hundreds of times more. But the real surprise was seeing them in person, at that scale, where his fluid and wonderfully authentic style was fully revealed.

His house—the house Hockney drew—wasn't in The City. It wasn’t in his hometown either. You can feel like a stranger in any corner of the world, but if you start drawing that very place, you'll get closer to it, and perhaps—only perhaps—you might be able to stop time. Your time. Or, at least, and for a fleeting moment, you might feel at home.

I can’t stop time, as Ilu Ros wishes in her story—which is also, in a way, a little bit my own too—but, at least, I can expand space. I have always thought that my home was wherever my books were stored, so I choose to believe I am doubly lucky: I have two homes in two places, instead of just one.

One here, and one there.

Go and read Ilu Ros’s book — highly recommended! ❤️

✏️✨

Happy sketching!

Ana

I'm delighted to read your post in both languages, Ana. My Spanish is not very good but I think I can improve it if you continue to do this, hahaha!

So nice to see Xativa... I visited this place many times and enjoyed walking up the hillside to drink a refresco while looking back over the town. What a lovely place. But, as you say, it has sort of stuck in time. Whereas London is always changing.

Thanks for the reference to Hockney's work. Always a treat to think about him.